Privacy and Security Policy Model

Privacy and security standards specifications describe the capabilities needed to manage the privacy and security policies in support of health information exchange. Security policies stipulate the administrative, physical, and technical mechanisms required to enforce jurisdictional and organizational health privacy policies both generally and as they may be expressed in a healthcare consumer’s consent directives.

In the context of electronic health information exchange, the management of privacy policies migrates from being strictly an administrative paper-based function (“out-of-band” capability) to enablement as technical functions (“in-band” capability), the administration of which becomes the management of electronically expressed privacy rules that can be interoperably communicated as well as computably negotiated and executed. As the expression of privacy policies matures from paper-based formats to unstructured electronic formats, and finally to structured, interoperable and computable formats, our ability to enlist security mechanism to enforce these policies will be proportional to our alignment of the structured expressions of security and privacy rules.

For example, a privacy policy may dictate that a consumer has the right to create and update a consent directive. If that policy describes this rule in terms of a consumer as a security principal with rights assigned to a role (consenter) with permission to perform certain operations (create and update) on an object or resource (the consent directive), then the security policies of the entity controlling access to the consent directive resource can unambiguously enforce this privacy policy. Another example is in the case of an emergency, where the capability to alter access privileges set by privacy policy to the appropriate level (failsafe/emergency access) may include an override of a consumer’s consent directive based on the security attributes of the principals involved. Among the standards available today to electronically express security and privacy policies, we have found a convergence toward standards for the expression of security policies required to adjudicate and enforce interoperable privacy policies/consent directives.

Information Policy Management

This discussion follows the ISO 22600 Health Informatics – Privilege Management and Access Control and the current working draft of that standard by developing a conceptual structure or “ontology” for relating privacy and security policies in a manner that facilitates the selection of development of technical standards and vocabularies necessary to implement the privacy policies.

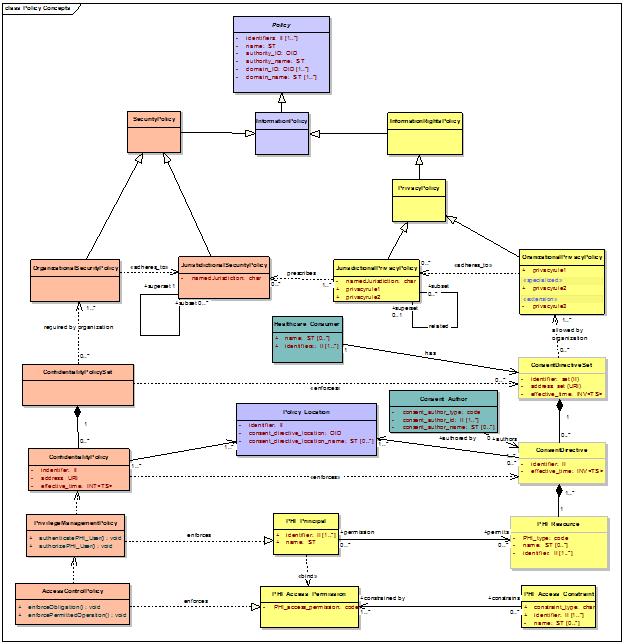

The ontology, illustrated in the concept diagram below, begins at the most generic level of “policy” and proceeds to specialize that class in order to derive the components necessary to the technical privacy and security policy framework for managing and controlling access to health information.

Information Policy Management is the means by which an information domain shares information internally or externally in accordance to policies to which one or more relevant domain authorities require compliance.

An information domain is a conceptual construct that consists of a set of information, entities or “principals” that have an interest or “right” in the information, and information policies dictate and protect those rights. Specifically, security policies safeguard the information (a valued resource) and enforce information rights policies that institute the rights of principals in information and dictate how those rights may be exercised.

Interoperability within and among complex information systems requires the ability to convey and enforce domain information rights policies by binding these to applicable security policies in a manner that can be executed by conformant systems within the domain and negotiated among conformant systems outside the domain. To accomplish this, the relationship among these policies needs to be articulated through shared conceptual models and terminologies that enable the comparability among policy components needed for policy communication and harmonization. To that end, we initially model the relationship of generic information rights and security policies, and then specialize with respect to personal information, and then further specialized to personal health information. These models will form the basis for specifying currently available information exchange and terminology standards needed to implement interfaces used to convey and enforce these policies and delineating gaps requiring future standards development.

By means of a domain information rights policy, a principal with an ownership right in or control of information may grant another principal the right to access that information for some specified use and under certain conditions by means of issuing a license. The license may stipulate:

- The nature of the information by type or instance

- The principals or types of principals (roles) that are authorized under the license

- The rights or operations that may be performed on or with the information

- The conditions for exercising the right, such as:

- The purpose for which the information will be used

- The medium, mechanism, or location by which it may be accessed

- The time interval during which or frequency with which a right may be exercised

- Any obligations that incurred by the licensee, such as:

- Payment for the license

- Auditing of the exercise of the license

- Assurance of compliance with the license

- Limitations on uses of the information beyond those granted in the license

A principal may delegate the right to grant a license to a delegate such as a legal representative, and may delegate the issuance of such licenses to a third party license issuer. The domain’s information rights policy is enforced by a domain’s information security policy, which controls access to and permitted operations on the information by authorized principals in accordance with the information rights policy.

Where the domain information includes personal information, information rights policies will likely include compliance with jurisdictional and/or organizational privacy policies. Privacy policies are specialized information rights policies that enable, to the extent permitted by superseding interests, e.g., national security, a principal who is the subject of personal information to exercise certain rights to control, for example, the collection, access, use, and disclosure of information about the subject.

A jurisdictional privacy policy may be comprised of the union of non-conflicting jurisdictional privacy policies, e.g., with respect to health privacy, the union of HIPAA and other federal privacy laws, e.g., as enacted in 42 CFR Part 2 for Substance Abuse Program information, Title 38 Section 7723 for Veterans’ Administration, or 42 CFR 431.301 for the use of Medicaid Applicant and Recipient information. In addition, a jurisdictional privacy policy could be comprised of the non-conflicting union with cross-jurisdictional privacy policies, e.g., an EU member nation’s privacy policy with the EU Privacy Policy.

A privacy policy that follows an “opt-in” model gives the principal who is the subject of personal information or the principal’s delegate the right to explicitly grant a license to that information for specific uses to another principal. A privacy policy that follows an “opt-out” model gives the principle who is the subject of personal information or the principal’s delegate the right to explicitly withhold a license to that information for specific uses by another principal.

A principal who is the subject of information may exercise privacy rights by granting or withholding consent, in accordance with overarching jurisdictional and/or organizational privacy policies by asserting a specialized license in personal information or “consent directive” e.g., a consumer’s privacy right to opt-out of personal information sharing financial information .

With respect to personal health information (PHI), a principal’s consent directive is a “personal” health privacy policy that is a specialization of the overarching jurisdictional and/or organizational privacy policies that are in effect. For example, the PHI Subject may have one or more privacy rights to control collection, access, use, and disclosure of PHI to the extent permitted by superseding interests, e.g., public health.

A principal who is a healthcare consumer may author multiple consent directives in accordance with multiple organizations within one or more jurisdictions. The consent directives may be recorded in one or more consent repositories, for example, in a personal health record repository and in one or more providers’ electronic health record systems. Together, these form the healthcare consumer’s consent directive set. The consent directives may be indexed by one or more consent directive registries, which may be stored within a healthcare consumer identity registry or as part of a health record index, and may be accessible by health information exchange record locator services.

Of note are the differences between information rights policies at the jurisdictional or organizational levels and policies that are asserted by rights owners/principals. Jurisdictional and organizational information rights policies should, in theory, result in a consistent and somewhat stable overarching set of rules that have applicability within some governance space (rights governance level). In contrast, personal information rights policies are by nature manifold, changeable, and likely inconsistent. These differences impact information exchange requirements. Both levels require capture, management, communications and negotiation, and should be enabled by automated and interoperable mechanisms. However, principals asserting rights need the ability to change multiple factors relating to their assertions easily and in real time, and to manage inconsistencies among assertions and negotiate the differences between what they are permitted to assert in different jurisdictions or organizations.

Interoperability within and among complex health information systems requires the ability to convey and enforce jurisdictional, organizational, and personal privacy policies (consent directives) by binding these to applicable “confidentiality policies”. Confidentiality policies are specialized security policies that enforce jurisdictional, organizational, and personal privacy policies, which are in addition to security policies required to meet non-privacy related information rights policies. The applicable security policies may be comprised of a non-conflicting union of intra- or cross-jurisdictional security policies, and organizational security policies.

With respect to any type of healthcare consumer consent directive that may be specified in accordance to an organization’s privacy policy, there may exist one or more confidentiality policies necessary to enforce the consent directive.

The required confidentiality policies specify the privilege management policies necessary to enforce consent directive authorizations and the access control policies necessary to enforce the consent directive access permissions and any associated constraints on those permissions in the form of conditions on the permission or obligations on the privileged principal.

There exists an exhaustive set of confidentiality policies required to enforce the consumer’s set of consent directives. When sharing the consumer’s PHI outside of an organization or jurisdiction, conflicting confidentiality policies may require policy bridging, which may be conducted via in-band and out-of-band negotiation mechanisms. For example, one jurisdiction or organization may refuse to share protected personal information with another that has less restrictive protections unless the receiving party agrees to enforce at least some of the sending party’s confidentiality policy.

Until policy models and structured terminologies are standardized and semantically interoperable conveyance of policies is supported, policy bridging must be negotiated “out-of-band” by non-automated means. Once these standards are fully developed and widely adopted, automated policy bridging or “in-band” algorithmic negotiation will be possible.

A final note on Privacy and Security Policy Management: The capability to electronically enforce obligations imposed by consent directives on principals downstream from the initially authorized recipient principal is of particular interest for future work. Within U.S. healthcare, there is an expectation that HIPAA compliant covered parties will enforce certain obligations on downstream business associates via out-of-band contractual mechanisms. While the actual enforcement is difficult to ascertain, the cost of doing so is higher than it needs to be given “in-band” approaches that might be used. With the convergence of electronic expressions of security policies and privacy policies, including consumer consent directives, the enforcement of obligations might follow the “in-band” mechanisms used by other industries that electronically enforce rights in and permission to access digital resources by way of digital rights management (DRM). Such mechanisms are deployed by tagging resources with owner designated digital rights, issuing licenses to authorized principals, and embedding enforcement in the “rights aware” applications necessary to access the resources. Under this paradigm, healthcare consumer consent directives would result in the tagging of the consumer’s PHI with rights that could only be exercised by licensed principals through rights aware applications. DRM would enable the consumer to specify downstream uses, e.g., the PHI may be used for claims payment and institutional review board (IRB) approved research, but not for profiling the prescribing patterns of providers.

Although DRM is a robust market-tested and market-accepted technology in non-health care arenas, it has yet to be widely deployed here despite being recommended in testimony to NCVHS . Despite well known flaws with non-health implementations of DRM namely, the preponderance of proprietary “rights aware” applications and ease of breach, those issues are less problematic in healthcare where CCHIT certified applications should eliminate any vendor’s interest in proprietary client side software and where better than the “80-20” rule holds; that is, someone may want to take digital photographs of the monitor displaying a VIP’s health information, but health information data aggregators are unlikely to circumvent the consent directives of the majority of healthcare consumer records without permission.